History of the discovery of the species

A small inhabitant of the highlands of Latin America was first described by a scientist from Italy, Emilio Cornalli, in the middle of the nineteenth century.

This animal is so secretive that even today there are simply no reliable facts about its way of life.

In 1865, scientists also demanded unconditional facts proving the existence of a mysterious animal, but apart from the skins of animals that occasionally appeared in Indian markets, there was nothing to present to the world community.

It was only in the 90s of the last century that photographs of Andean cats appeared, and at the end of the century the elusive animal was tracked down by researcher and naturalist Jim Sanderson on the border of Peru and Chile. The scientist was able to approach the predator at arm's length and take a series of photographs. At the same time, the Andean cat completely ignored the person and did not show any signs of aggression.

A pair of Andean mountain cats was found at the beginning of this century in the Argentine reserve Caverna de Las Brajas.

Moreover, one of the specimens was a female with cubs, hiding in a small cave high in the mountains. The reserve employee even managed to take a few photographs.

In 2004, in a national park in Bolivia, one such cat was even captured and radio-collared. Observations were carried out for no more than a year, were very meager and only made it possible to confirm the nocturnal lifestyle of the small predator. Soon the individual died in a poacher's trap.

All researchers note that it is impossible to see the same animal twice. The distrustful and secretive animal immediately changes its location after the slightest contact with a person.

Nevertheless, the description made by an Italian scientist in 1865 is fully confirmed based on accumulated facts.

According to the testimony of South American Indians, earlier populations of these animals were more numerous, but cats were simply stoned to death as soon as they approached human camps.

For some reason, killing this animal was considered the greatest achievement. No one has ever managed to tame the distrustful predator. The Indians reported that in captivity the Andean cat is not able to live even a year, it refuses food and water, and simply dies.

Apparently, this attitude of people has developed in the predator a stable habit of carefully hiding, as well as migrating to the most inaccessible mountainous areas.

Most likely, the population of Andean mountain cats is the smallest on Earth and barely amounts to two and a half thousand individuals.

Mr. Cat recommends: characteristics, habitat

The Andean mountain cat (Leopardus jacobitus) is a small, high-altitude wild cat that is now listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List because there are fewer than 2,500 specimens of the creatures alive in the world, scientists believe. , still exist in the wild.

The species was first described by Emilio Cornalli, who named it after the Jacobite Mantegazza.

The Andean mountain cat has ash-gray fur, a darker shade of the head, ears and muzzle. The areas around the lips and cheeks are white, with two dark brown lines running from the corners of the eyes through the cheekbones. There are several black spots on the front legs, yellowish-brown markings on the sides, and up to two narrow dark rings on the hind legs. The long, bushy tail has 6 to 9 rings, ranging from dark brown to black.

The markings of the young are darker and less pronounced than those of sexually mature individuals. The skulls of adults range from 100.4 to 114.8 mm or more in length, and are somewhat larger than those of Pampas and domestic cats.

The Andean mountain cat has a black nose, lips and rounded ears. On the back and tail the hair is 40-45 mm long. Its rounded toes are 4 cm long and 3.5 cm wide. The paw pads are covered with hard hairs, which allows it to move on hot rocks in summer or cold rocks in winter.

The size of adult individuals varies from 57.7 to 85 cm in length from head to rump, long tail from 41.3 to 48.5 cm. Height at the withers is about 36 cm, and body weight is up to 5.5 kg.

The South American mountain cat lives only at high altitudes in the Andes. Camera footage from observers in Argentina, only made public in 2000, shows it ranges in altitude from 1,800 m above sea level in the southern Andes to over 4,000 m in Chile, Bolivia and central Peru.

The area is extremely arid, with sparse vegetation, rocky and steep. The Andean cat population of the Salar de Surire Nature Reserve was estimated at five individuals in an area of 250 square meters. km.

A survey of observers and local people in the province of Jujuy in northwestern Argentina indicates densities of 7 to 12 individuals per 100 square meters. km. at an altitude of about 4200 m above sea level.

Andean mountain cats are found locally. Their Andean habitat is fragmented by deep valleys.

Scientists in some scientific classifications classify the Andean cat as a separate genus Oreailurus, but official ones still classify it as a tiger Leopardus, which also includes their closest relative Ocelot.

Security status

In 2002, Andean mountain cats were moved from being listed as vulnerable to being listed as endangered. The species is listed in the IUCN Red Book and the CITES list - the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Peru, Argentina and Bolivia prohibit the hunting, capture, possession, and trade of Andean cats live or in body parts. In Chile, hunting Andean and Pampas cats is punishable by a fine of up to $6,000, and for repeated violations - a prison term of up to 3 years. Of the 36 protected areas, evidence of the presence of a rare species was found in 24 regions, contacts are isolated.

Morphological differences between Andean and Pampas cats

The Andean mountain cat and the Pampas cat look almost identical. This makes it difficult to determine which animal is being observed and makes it difficult to properly estimate populations.

Pampas cat

This can be confusing when trying to get the correct information from observations of naturalists who have seen one of these cats but do not realize that they need to look for specific features to differentiate between the two species.

The characteristics of both types of small cats are shown in the table:

| Andean mountain cat | Features | Pampas cat |

| Two thirds of the total body length. Thick and blunt at the tip with 6-9 wide rings. | Tail | Half of the total body length. Thin and pointed at the tip, with 9 thin rings. |

| The maximum width of the ring marks is about 6 cm. | Ring markings on tail | The maximum width of the rings is 2 cm. |

| Characteristic lines on the sides of the eyes. Rounded ear tips. | Description of the muzzle | If stripes are present, they are brown and less pronounced. Triangular-tipped ears are characteristic of most representatives of this species. |

| Very dark or black. | Nose | Light, usually with pink lobe. |

| Yellowish, rusty or grayish and charcoal shades. | Color | Beige, cream, reddish, rust and anthracite colors. |

| One consistent pattern type. | Markings | Three different fur patterns with different variations. |

| Uniform coloring of the main color. | Ear color | Patterned colored ears. |

| The rings are not completely closed, the stripes look like spots. | Front paw coloring | Two or more clear, full, black rings. |

Features of behavior

The usual climatic conditions for Andean cats are rocks, high mountain ranges, steep mountain slopes, dry, cold or too hot air, low rainfall.

The environment has made this predator a creature with a high degree of survival in conditions of hot summers and very cold winters, an almost complete absence of flora and water sources. Although outwardly the Andean cat is not very different from its domestic relatives, it is an extremely hardy animal that can safely enter into battle with an enemy superior in strength and size.

This is an extremely dexterous and maneuverable creature that moves without fear along almost vertical rocks, is not afraid of enormous heights, easily overcomes any obstacles, performing incredible somersaults and jumps in the air, changing the direction of movement right in flight.

The Andean cat has a perfect hearing aid that allows it to detect the slightest rustles of potential prey and enemies.

The animal's vision and sense of smell are also excellent. In behavioral reactions, this animal is similar to its Pampas counterpart, with which it periodically intersects in its native habitat.

This is a characteristic nocturnal solitary predator that mates only during the mating season.

Recent research by scientists suggests that the hunting grounds of each Andean predator occupy from 35 to 70 square meters. km. Their border is marked by physiological secretions and scrapes, which are periodically renewed. At the same time, the territories of male and female individuals, unlike representatives of other cat species, do not overlap.

The animal practically blends in color with the mountain landscape due to its grayish color, so it is very difficult to detect.

An excellent balancer – a long and thick tail – helps the animal change the direction of its jump in the air. Thick and dense fur perfectly protects the cat from the harsh winter.

The animal is content with a small amount of moisture, which it obtains mostly from melted mountain springs and from living food.

Read: 47 representatives of the cat family and their photos.

Diet

Mountain Andean cats are secretive and cautious hunters; there is only speculative information about their diet. Most likely, this is an extremely poor choice due to the small amount of potential prey in the animal’s natural habitats:

- The mountain spotted viscacha is a large rodent, weighing up to three kilograms, resembling a rabbit in appearance.

- The chinchilla is a crepuscular rodent that lives in colonies.

The Andes Mountains are home to six different species of predators, three of them being cats, the Andean cat, the Pampas cat and the puma.

Of these, the puma is a large predator, and the Andean cat and the Pampas cat are medium-sized predators and are very similar. They both hunt in the same territory and the same prey due to the low genetic diversity of the area.

Vizcacha accounts for 93.9% of the biomass consumed in the Andean cat's diet. This is due to the fact that there are significantly fewer other prey objects, in addition, these rodents also lead a crepuscular lifestyle. And the Pampas cat depends on Vizcacha by 74.8%.

In some areas, the mountainous Vizcach will account for 53% of the Andean cat's production.

By the way, researchers believe that in those areas where there are few colonies of viscachas and chinchillas, Andean cats can hunt during daylight hours.

Cultural significance

Bolivians consider the titi to be a sacred animal. Locals perform various rituals for good luck using body parts, skins or stuffed Andean and Pampas cats. The former promise a successful harvest, protect livestock from disease, and silver “kolke-titi” attract wealth.

Villagers believe that Andean cats belong to Pachamama, the goddess who personifies Nature. If upon meeting her pet is friendly towards the person, the next year will go well. If a cat hisses or attacks, expect trouble. The hunter who killed the cat finds himself in Pachamama's debt. He must repay her by performing a religious ritual.

A stuffed animal is made from the prey - the skin is filled with wool, decorated with ribbons, colored threads, coins, and coca leaves. The remains are buried at the site where the cat died. The shaman illuminates the effigy, which the hunter and his family will worship for many years to come. As long as the totem is treated with respect, men can go fishing without fear of the wrath of the goddess.

Members of the Andean Cat Union conduct educational activities among the local population, bringing state laws to remote communities, explaining the importance of preserving rare species. Together with government officials, they participate in organizing agricultural activities and tourism in areas important for the revival of the population.

Puberty and reproduction

Thanks to observations by residents of the Andean mountains of cats paired with the opposite sex and with kittens, it can theoretically be assumed that the predator's mating season lasts from July to August. Since kittens were spotted in April and October, it is believed that the mating season may extend into November or even December.

A litter usually consists of one or two kittens born during the spring and summer months. This is typical for many other cat species, which also give birth to young during periods when food supplies are sufficient.

Puberty, as scientists suggest, occurs in animals closer to two years, and the average life expectancy does not exceed ten years.

Keeping the Andean cat in captivity

This rarest animal in the world is not kept in any zoo in the world.

Besides the fact that the Andean mountain cat is extremely difficult to catch, it simply does not survive in captivity.

Information about the residence of these cats in nature reserves and national parks of South America is extremely rare.

This animal is strictly protected, so its illegal resale is punishable by law in the same way as hunting it or trading in skins and any other body parts.

Lifestyle

The habits and lifestyle of Leopardus jacobitus are poorly understood. Like most other felines, they are solitary, territorial animals. When meeting with a fellow tribesman or potential enemy, they prefer to avoid the conflict.

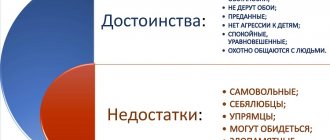

Character

Andean mountain cats are not shy - when meeting people, if they do not try to catch the animal, they do not pay attention to the person. Several zoologists were able to observe hunting, the process of marking territory, play, and serene sleep on a stone. The cats saw them but did not show any concern.

In 2004, Bolivians put a collar with a direction finder on a captured female. This made it possible to establish that Andean cats exhibit increased crepuscular activity. Assumptions about a nocturnal lifestyle were not confirmed - during the day they also cover considerable distances. Perhaps this is due to the depletion of hunting grounds.

Population protection

In 2002, the Andean cat's status was upgraded from Vulnerable to Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

As the habitat spread across four countries, biologists attempted to collaborate in efforts to protect the species. One of the groups formed was the Committee for the Conservation of Andean Cats, now known as the Andean Cat Union.

The direct threat to these predators is loss of habitat, and the indirect threat is various forms of land use, including mining and water extraction, which could potentially increase as a result of climate change.

Also dangerous are inappropriate pastoral and agricultural practices, unregulated tourism, secondary mineral and water extraction, and oil and gas extraction.

A separate point in preserving the species is in resolving conflicts with small livestock farming, in the fight against insufficient knowledge of the species by members of the local community, protection from dogs, accidental exposure to traps.

Scientists paid special attention to the fight against the religious use of Andean cat skins and taxidermy, hunting animals according to traditional beliefs and superstitions.

The Andean cat's habitat spans four different countries in South America. Each has enacted individual laws to protect this endangered animal.

Each country also has its own protected areas where hunting any animals is completely prohibited.

Naturalist Jim Sanderson is still concerned about the fate of the Andean cat.

Through his efforts, together with Constanza Napolitano, Lilian Villalba, Eliseo Delgado and other researchers, a conservation agreement was concluded between the Andean Cat Union and the non-profit organization Fundación Biodiversitas and the government agency CONAF, responsible for the management of national parks and industrial forests.

Villalba of the Andean Cat Union conducted a major research program, including radio telemetry studies, in the Jastor region of southern Bolivia between 2001 and 2006.

Links[edit]

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Species Leopardus jacobitus". In Wilson, Delaware; Reader, D. M. (ed.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographical Guide (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ abcde Villalba, L.; Lucerini, M.; Walker, S.; Lagos, N.; Cossios, D.; Bennett, M., and Huaranca, J. (2016). "The Jacobite Leopard". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

.

2016

: e.T15452A50657407. Retrieved October 29, 2022. - McDonald, D.W.; Loveridge, A. J., & Nowell, K. (2010). “Dramatis personae: introduction to wild cats. Andean cat Leopardus jacobita (Cornalia, 1865)". In Macdonald, D. W. & Loveridge, A. J. (eds.). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids

. Oxford: Oxford University Press. paragraph 35. ISBN 978-0-19-923444-8. - ^ abcd Yensen, E.; Seymour, K. L. (2000). » Oreailurus jacobita » (PDF). Species of mammals

.

644

(644):1–6. DOI: 10.1644 / 1545-1410 (2000) 644 <0001: O.Yu.> 2.0.CO; 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2015. - ^ abc Garcia-Perea, R. (2002). "Andean mountain cat, Oreailurus jacobita: morphological description and comparison with other felids from the Altiplano". Journal of Mammology

.

83

(1):110–124. DOI: 10.1644/1545-1542 (2002) 083 <0110: amcojm> 2.0.co; 2. - Jump up

↑ Palacios, R. (2007). Guide para Identificación de carnívoros andinos. Alianza Gato Andino, Cordoba, Argentina. 40 pp. - Nowell, K., & Jackson, P. (1996). "Andean mountain cat, Oreailurus jacobitus (Cornalia, 1865)" (PDF). Feral Cats: Status Review and Conservation Plan

. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 116–118. - Sorley, L.E.; Martinez, F.D.; Lardelli, W., & Brandi, S. (2006). "Andean cat in Mendoza, Argentina - further south and at the lowest altitude ever recorded." Cat News

(44): 24. - ^ abc Napolitano, C.; Bennett, M.; Johnson, USA; O'Brien, S. J.; Marche, Pennsylvania; Barría, I.; Poulin, E. and Iriarte, A. (2008). "Ecological and biogeographical inferences of two sympatric and cryptic Andean cat species using genetic identification of fecal samples." Molecular Ecology

.

17

(2):678–690. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03606.x. PMID 18205675. S2CID 8517958. - ^ab Villalba, M.L.; Bernal, N.; Nowell, C. and McDonald, D.W. (2008). "Distribution of two small Andean cats (Leopardus jacobita and pampas cat Leopardus colocolo) in Bolivia and the potential influence of traditional beliefs on their conservation" (PDF). Endangered Species Research

.

16

(1):85–94. DOI: 10.3354/esr00389. - ^ ab Cossios, DE; Madrid, A.; Condori, J. L., & Fajardo, U. (2007). "Updated information on the distribution of the Andean cat Oreailurus jacobita and the pampas cat Lynchailurus colocolo in Peru". Endangered Species Research

.

3

(3): 313–320. DOI: 10.3354/esr00059. - Reppucci, J.; Gardner, B. and Lucerini, M. (2011). "Estimates of Andean cat detection and density in the high Andes". Journal of Mammology

.

92

(1):140–147. DOI: 10.1644/10-MAMM-A-053.1. - Walker, R.S.; Novaro, A.J.; Perovic, P.; Palacios, R.; Donadio, E.; Lucerini, M.; Pia, M. and Lopez, M.S. (2007). "Diet of three Andean carnivore species in the Argentine high desert". Journal of Mammology

.

88

(2):519–525. DOI: 10.1644/06-Mamm-a-172r.1. - Lucerini, M. (2009). "Activity Pattern of Predator Separation in the High Andes". Journal of Mammology

.

90

(6):1404–1409. DOI: 10.1644/09-Mamm-a-002r.1. S2CID 76656004. - Cossios D.; Beltrán Saavedra, F.; Bennett, M.; Bernal, N.; Fajardo, U.; Lucerini, M.; Merino, M.J.; Marino, J.; Napolitano, C.; Palacios, R.; Perovic, P.; Ramirez, Y.; Villalba, L.; Walker, S., & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2007). Methodology manual for relevant carnivoros alto andinos

. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Alianza Gato Andino. - ^ ab Palacios, R.; Villalba, L., ed. (2011). Plan Estratégico para la Conservación del Gato Andino, 2011–2016. (PDF). La Paz, Bolivia: Alianza Gato Andino.

- ^ ab Villalba, L.; Lucerini, M.; Walker, S.; Cossios, D.; Iriarte, A.; Sanderson, J.; Gallardo, G.; Alfaro, F.; Napolitano, C., & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2004). Action Plan for the Conservation of Cats in the Andes (PDF). La Paz, Bolivia: Andean Cat Alliance.

Interesting facts about the Andean cat

The Andean mountain cat is the rarest and least studied animal in Latin America, despite the fact that it has been known to people for a very long time.

One of scientists’ versions of the degeneration of the species is a sharp decline in the populations of mountain chinchillas.

The local population of Chile and Peru has been trying to catch the Andean cat for many years, but almost no attempt has been successful.

Due to the impossibility of keeping the Andean cat in captivity, there is no possibility of creating hybrid species or artificially increasing the population size.

1111

Threats

It is not clear whether the rarity of the Andean cat is a natural phenomenon or due to human actions. Skins of this species have been spotted in local markets, and the animals are sometimes killed by shepherds who carry weapons. There are no records of international trade in this species. Therefore, it is believed that the hunting of Andean cats is primarily carried out to protect local livestock. The global threat of habitat destruction does not apply here, as there have been no significant changes in land use in the Andean highlands over the past 2,000 years. If anything, the human population has decreased in these regions. It is possible that the Andean cat population has declined due to hunting of mountain chinchillas and mountain viscachas, which naturally have patchy distributions.